#11 - Compounders, Deep Value and WildBrain

Last updated: Nov 1, 2022

Disclaimer: I own shares of the securities mentioned here. I may sell these at any time and without notice. Nothing here is investment advice. Do your own due diligence.

When we talk about compounders in the investment realm, we usually mean high quality companies that can consistently compound shareholder wealth at a superior rate over the long-term (from a Morgan Stanley article).

From the article:

The key financial characteristic of compounders is that they enjoy sustainable, high return on invested capital (ROIC).

In other words, a compounder can be recognized or detected ex-post by looking at its ROIC, which leads to increased book value overtime, etc.

That’s the descriptive definition a compounder: a compounder is a business that has been compounding shareholder value for a long period (define “long” however you wish).

But then we have to understand whether the high ROIC is sustainable, or if we should expect reversion to the mean.

In other words we must determine why the compounding occurred. From the same article:

We believe that companies with strong franchise quality have a sustainable competitive advantage by virtue of their intangible assets, which competitors generally have difficulty re-creating or duplicating. These dominant and durable intangible assets may include strong brand recognition, which tends to be driven by innovation, customer loyalty, copyrights and distribution networks.

Many investors look at compounders through the descriptive definition, and use that to predict that they will keep compounding. While fundamentally flawed in theory, often enough, this approach turns out to be practically right, as long as the historical compounding has lasted for a long enough period of time.

The reason that this approach works in practice is that as the compounding period grows longer and extends over several cycles, the probability that the resistance to entropy and decay was due to sheer luck gets exponentially smaller.

Therefore, long historical compounders typically have some kind of unique growth engine within. Alternatively, they have a great capital allocator at the helm (think CSU.TO or BRK).

The latter is an example of manual compounder, where the compounding happens thanks to the discrete decisions of a person or a group of people. Apple, on the hand, is an example of automatic compounder, where the compounding happens thanks to the brand power and oligopolistic position.

That leads us to the predictive description of a compounder: a compounder is a system with a positive feedback loop between its components.

The difference between the descriptive and predictive definitions of compounders is summarized perfectly here:

Many systems in the world exhibit the exponential behavior of a process feeding upon itself.They all contain the first-order linear positive feedback generic structure.

Imagine something happens that causes something else to happen - A causes B. Further, imagine that B also causes A. If A happens then B happens, but then A happens again, making B happen again. And on and on it goes. This is called a positive feedback loop.

The quintessential example of such a feedback loop is population growth: more adults forming couples leads to more births, a fraction of which which will lead to more adults forming couples.

Another example in business is word of mouth and brand power: more customers leads to them talking about the brand to other people, a fraction of which turn into new customers.

Or going back to our initial definition of a compounder business: a business that invests capital, a fraction of which (ROIC - WACC) returns as economic surplus to the capital pool.

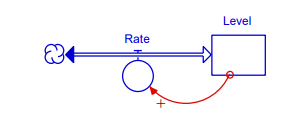

Here’s a generic picture of the simplest positive feedback loop imaginable, called first-order feedback loop:

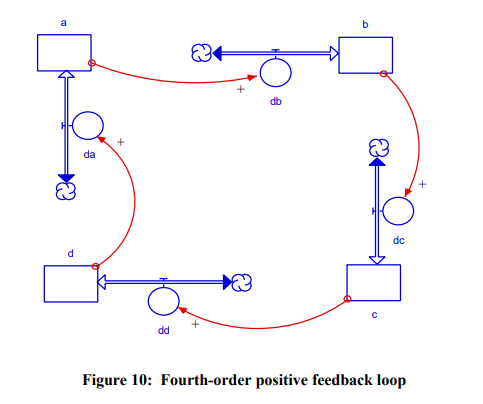

Compounding systems can be more complicated. Here’s an example of a fourth-order feedback loop (source):

The more I learn about WildBrain, the more I want to know about it.

This is probably the first company where I feel like I have a chance of acquiring a deep understanding of the business.

Here’s a tweet from Ho Nam that describes deep value in terms of understanding of the business rather than price discount:

I believe WildBrain is a deep value compounder that has not yet been identified as such.

A weird particularity of exponential growth is that in the beginning, it looks flat. But once it takes off, it goes vertical.

I think WildBrain is still in the “flat” zone. In their last investor day, someone asked the question: “If everything you’re saying about the company is true, why are the revenues still flat?”

I thought: “OK…am I crazy or do I have an edge here?”

Where edge, as per Joel Greenblatt’s definition, is simply a particular angle that gives you a differentiated insight.

My insight is this: not only am I not worried that revenues are flat, I’d be worried if they were growing fast already. I believe WildBrain is currently building the growth engine and setting up the proper feedback loops within. They are going for quality and long-term compounding deals instead of chasing one-offs. The growth will become obvious after a few cycles.

More concretely, the market will be surprised once the high-margin consumer products get going (with Peanuts, Strawberry Shortcake, and Sonic). But once again, it will take a couple of cycles of the loop for the inflection point to be visible.

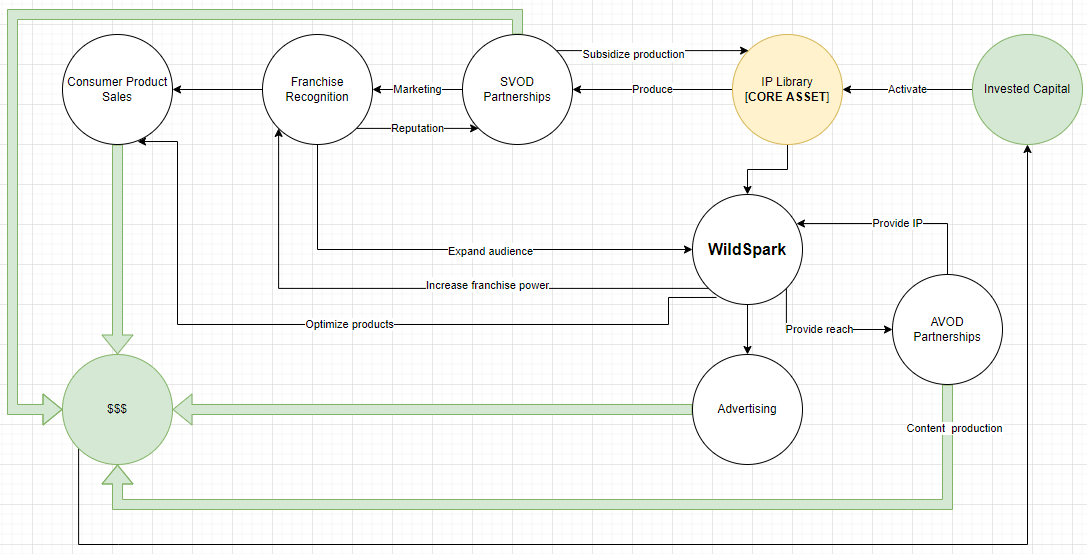

Here’s a simplified diagram depicting WildBrain’s compounding power. Notice the multiple internal feedback loops at work.

Fitch Revises Outlook for WildBrain to Stable

Old West Investment Thesis (letter of 2018Q3)

Links about compounding and positive feedback loops:

https://www.reforge.com/blog/growth-loops

https://untools.co/reinforcing-feedback-loop

https://www.click-360.com/vlog/positive-feedback-loops/

Disqus comments are disabled.